Several partners and potential partners have asked me about how value investing works in an expensive market.

Since the 2009 bottom, the market has run-up considerably. This run-up creates angst and anxiety among investors. The natural question is: in an expensive market, do opportunities still exist for value investors? Absolutely.

In the United States, there are roughly 5,000 listed stocks that are large and liquid enough to invest in. Of these 5,000 stocks, at any given moment, some will be undervalued, some will be fairly valued, and some will be overvalued.

Our fund targets an absolute, long-term return. As a result, all stocks we purchase must clear an absolute return hurdle, before we will invest in them. Our return hurdle is simple: for us to buy a stock, we must believe that it has the potential to double to triple in price over the next 2-3 years, while posing a minimal risk of permanent loss of capital.

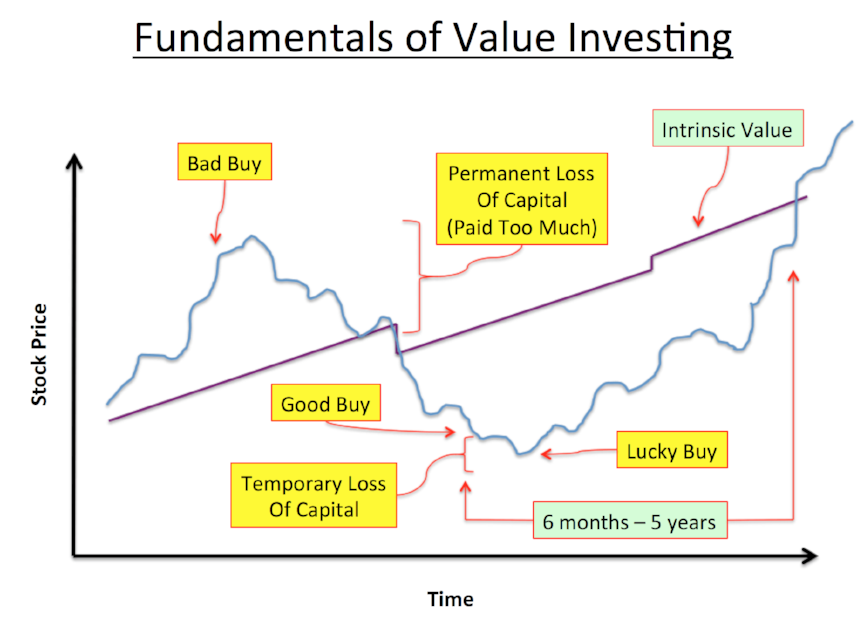

In a cheap market, many stocks will clear this return hurdle, making my job easy. In an expensive market, like our current one, very few stocks will clear this return hurdle, making my job more difficult. (See the chart below.)

In both situations, however, some securities exist which meet our buying criteria. Even when an expensive market narrows our pool of prospects, we still have some bargain securities to choose from. Remember, out of the 5,000 U.S. listed stocks, we only need to find 10 bargains to fill our portfolio. We can accomplish this even in an expensive market. There is a bear market somewhere.

Over time, undervalued stocks move towards fair value, overvalued stocks move towards fair value, and fairly valued stocks become either overvalued or undervalued. Stock prices fluctuate up and down. For instance, for the average stock, its yearly high is 30% above its yearly low. Clearly, the value of the underlying business did not fluctuate this much, but the stock price did.

To put value-investing in an everyday context, imagine that your neighbor Joe approaches you. Joe offers to sell you his home for half of what you know you could sell Joe’s home for in three years. Without hesitation, you immediately accept Joe’s offer. You don’t stop to check the price of the S&P 500, nor do you consider the status of any global military conflicts. You don’t even look up what changes to the Federal Reserve policy might occur. You see Joe’s bargain for what it is, and you capitalize on it.

Now imagine that a different neighbor, Paul, stops by the day after you buy Joe’s home. Paul offers to sell you his home for one-third of what you could sell it for in three years. Probably, you regret that you weren’t lucky enough to receive Paul’s offer first, but still, you never question that you got a good bargain in buying Joe’s home.

Value investing functions in the same way, but with one twist. Suppose that you receive bids, every single day, from potential buyers of Joe’s home. You don’t have to sell them Joe’s home, but you do have to look at their daily bids. Undoubtedly, these bids will fluctuate up and down (sometimes drastically), depending on which people bid, or on how many people bid, or on how the people felt when they bid. Often, their daily bids will not reflect the intrinsic value of Joe’s home. As the owner of Joe’s home, your job is to only accept the bids, once they reflect what you know Joe’s home is worth. Until you receive a bid above the intrinsic value of Joe’s home, it is best to tune out the noise of the daily auction.

As value investors, we do not buy pieces of paper (“stocks”). Instead, we buy pieces of businesses. Our job is to seek out an above-average business being sold at a below-average price, then wait for the business’s market price to reflect its intrinsic value. With 5,000 U.S. businesses being auctioned off each and every day, there will always be a few screaming deals.

David R. “Chip” Kent IV, PhD

Portfolio Manager / General Partner

Cecropia Capital

Twitter: @chip_kent

Nothing contained in this article constitutes tax, legal or investment advice, nor does it constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security or other financial instrument. Such offer may be made only by private placement memorandum or prospectus.