What is reality? While this question sounds arcane, I believe it delivers valuable insights into recent events.

We can answer the question, “What is reality?” from two approaches. The first approach is objective reality: reality is what I, as an impartial observer, can actually, empirically, or factually verify, regardless of how I feel or think about those facts. The second approach is consensus reality: reality is what my “tribe” believes to be, decides is, or treats as real. Consensus reality replaces facts that are objectively true, with facts that feel true. In consensus reality, if facts are inconvenient or antagonistic to the tribe’s beliefs, feelings, or opinions, then the tribe ignores, discards, or discounts them as “fake,” lies, or propaganda.

Consider the conflict between objective vs. consensus reality in the critical scientific question of the early 1600s: Which was the center of the solar system: the Earth or the sun?

Galileo embraced objective reality. After Galileo used his telescope to see the moons orbiting around Jupiter, he concluded that, in a similar way, the Earth must revolve around the sun.

By contrast, the Catholic Church favored consensus reality. Since the early 100s, the “tribe” -- in this case, the Catholic Church -- felt that the Earth stood still in the universe, and all heavenly bodies revolved around it.

Objective reality collided with consensus reality in 1610 when Galileo published The Starry Messenger. The Catholic Church attacked Galileo for spreading lies and heresy. In response, Galileo invited the church’s astronomers to look through his telescope, then decide for themselves. What happened next? As Galileo wrote to German astronomer, Johannes Kepler:

My dear Kepler, I wish that we might laugh at the remarkable stupidity of the common herd. What do you have to say about the principal philosophers of this academy who are filled with the stubbornness of an asp and do not want to look at either the planets, the moon or the telescope, even though I have freely and deliberately offered them the opportunity a thousand times? Truly, just as the asp stops its ears, so do these philosophers shut their eyes to the light of truth.

Sadly, the Catholic Church found Galileo “vehemently suspect of heresy” in 1633, and kept Galileo under house arrest until he died in 1642. In a sign of how durable the “group think” of consensus reality can be, the Catholic Church did not accept that the Earth revolved around the sun until 1822, 180 years after Galileo died.

How does objective vs. consensus reality relate to recent events? Let’s consider two examples: the January 6th attack on the US Capitol; and the recent frenzy in GameStop trading.

First, let’s examine the January 6th attack on the US Capitol. As I read about the people involved in the attack, I struggled to understand what brought together such disparate groups -- ranging from a) politicians; b) white supremacists; c) evangelical Christians; and d) conspiracy theorists who believe that Democrats are Satan-worshiping cannibalistic pedophiles (yes, really).

Why did such different groups band together in an effort to overthrow the results of the US election? Perhaps the best answer is consensus reality. As I discussed in last quarter’s letter, Rise Of The Machines, artificial intelligence is being used to target different media messages to each individual. These individually-targeted messages reinforced each “tribe’s” consensus reality that the US election had been “stolen” from Donald Trump, despite all objective evidence to the contrary. The desire to “right” this wrong spread through the groups like a social contagion, and ultimately, it erupted into actual violence. (Of course, violence has not been limited to the far right; last summer, violence erupted from the far-left as well.)

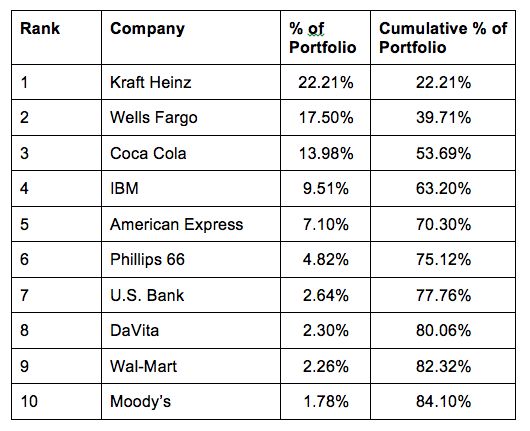

Second, let’s consider the recent frenzy in GameStop trading. In 2019 and 2020, GameStop was one of the most “shorted” stocks, meaning that investors who “shorted” its shares -- including well-known short-sellers like Andrew Left of Citroen Research -- believed that GameStop’s price per share would decrease. In a nutshell, their “short” investment thesis matched objective reality: GameStop’s brick-and-mortar business model is outdated, and over time, GameStop’s revenue and profits will decline.

But what about consensus reality? Thousands of “investors” belong to the WallStreetBets “tribe” on Reddit, an online message board. This “tribe” decided to launch a coordinated attack on highly shorted stocks, like GameStop.

The “tribe’s” investment thesis aligned with their consensus reality: let’s “stick it to the man” by buying a heavily shorted stock, driving its price higher, and triggering a short squeeze. (When a shorted stock stages a dramatic rally, it can be painful enough that short sellers are forced to exit from their positions. To exit from their positions, short sellers have to purchase back the shares at a loss. This pushes the stock sharply higher, in what’s known as a “short squeeze.”) As the WSJ wrote:

By early January, GameStop had moved from a stock recommendation to a phenomenon. GameStop was no longer only an opportunity for a big payday or a way to back a struggling company. Buying GameStop for some users had turned into a way to confront institutional money. Users encouraged others to hold the line: “Do not sell.”

This consensus reality, and the resulting short squeeze, drove GameStop’s price from $17 to $483 in less than a month. In this pump-and-dump scheme, the first in will do well -- if they sell early enough -- but the last in will get slaughtered. The “tribe” believes in the consensus reality of buying GameStop as a way of “sticking it to the man.” (As one “investor” told the WSJ, “Please tell the wolf of Wall Street that the pigeon of San Francisco is gonna eat your lunch.”) However, they can not overcome objective reality: GameStop’s business fundamentals can not support today’s price, and eventually, its stock price will collapse back to its intrinsic value.

What can we take away from the conflict between objective vs. consensus reality? First, without a common, objective reality, it will be difficult for our country to achieve long-term stability. This investment risk is real, and it will be with us for the long-term. Second, the pump-and-dump mob might have permanently eliminated the ability to short-sell obviously failing businesses. If this has happened, it will remove one of the checks and balances built into the market. Third, as your investment manager, I will continue to focus on objective reality: facts that I can impartially, accurately, and observably verify. As Howard Marks said:

Emotion is one of the investor’s greatest enemies. Fear makes it hard to remain optimistic about holdings whose prices are plummeting, just as envy makes it hard to refrain from buying the appreciating assets that everyone else is enjoying owning. Superior investors may not be insulated, but they manage to act as if they are.

Now that you know about it, where else do you see the conflict between objective vs. consensus reality?